Our Story

Warren Agnew

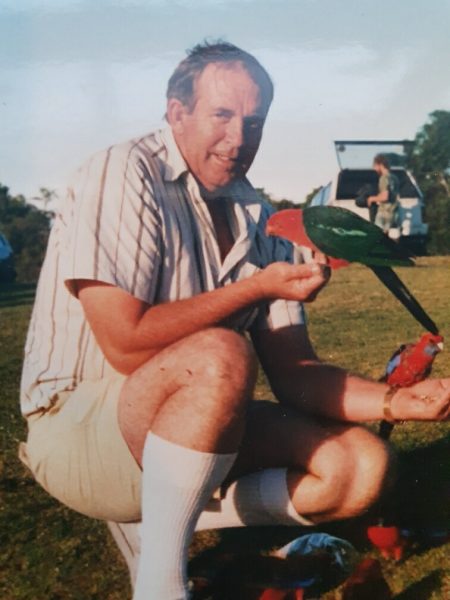

Warren Agnew was a passionate, determined conservationist and inventor of the Black Trakka.

Known for his long and entertaining conversations and always willing to share a story or an idea, he loved people of all walks of life and especially the different characters throughout New Zealand that shared his love and commitment to conservation. He was famous for his outrageous humour and his dogged debates – both with scientists in the lab, through to those hard workers out in the field. Along with the many hours and years he devoted, ultimately it was his ability to connect people and share ideas which led to the creation of this vital tool that is so fundamental to the fight against invasive species.

The Black Trakka is a system of tunnels with pre-inked tracking cards. A tool that appears simple at first glance, but a lot more technical than it looks, and one which took years to develop. For the practitioners in pest control, it is simple to use and it works – for the volunteers and forest rangers tracking small animals in the bush, through to high-level decision makers crunching numbers around the management table.

As a young man, Warren forged a love for the land through hunting and adventure within beautiful forests such as the Whirinaki and he later went on to explore every hidden corner of Aotearoa. He spent many years on the Mahurangi river, developing respect and an affinity for the ecosystems within it, and with years also spent as a school teacher within Maori communities he learnt a lot from the Maori culture and their appreciation for the whenua and our taonga species.

The first tracking systems in New Zealand used either ‘smoked paper’ or a system where the animal transferred one chemical in a sponge to another on a piece of paper, but these were complex to prepare. The early days of monitoring with ink involved ‘ink-it-yourself’ tracking cards which were a great innovation but were an awkward kit-set that needed to be assembled in the field and tended to dry out and so be ineffective. Tracking card potential though, was proven and a key landmark in the evolution of small animal monitoring was established by researchers studying the interaction between pest control operations and the subsequent breeding outcomes of the treasured kokako.

The researchers were able to monitor the abundance of rats in the forest with tracking cards and correlate the rat tracking results with kokako breeding to show that if rat numbers could be controlled to a sufficiently low level, a threshold was reached whereby kokako were able to successfully breed and increase their numbers.

However the ink-it-yourself systems, with their trays of food colouring or reactive chemicals and sponges, were messy and time consuming to set up, and the footprint tracks often bled terribly. And with so much crucial work needing to be done, an improved long-term solution had to be developed.

And so the evolution continued through a series of iterations and Warren was able to help take monitoring to the next level, developing pre-inked tracking cards that rangers could carry into the bush with them, ready to deploy as a quick and effective indicator to establish if their hard work was making any difference.

The Black Trakka monitoring system is a classic case of Kiwi ingenuity and “number 8 wire” mentality. Warren developed the system to a point where New Zealand’s Department of Conservation provided a supportive financial boost and expert advisers to help convert his vision into full operation.

It wasn’t just a simple case of having pre-inked cards. They needed to meet the needs of workers in the field and were developed over a long period of testing and modifications to ensure a long shelf and field life.

The ink had to be non-toxic for sensitive and treasured species such as lizards, frogs and weta; it needed the perfect viscosity to leave footprints, but not too sticky as to trap insects; and it also needed to be resilient to a wide range of environmental conditions, to stay moist out in the sun, but equally resist washing away in the rain.

The tunnels also had to be developed. A light and portable option was required – tunnels that could be carried into hard-to-reach areas and easily clipped together on site, and/or enabling a quick and specific layout of tunnels in response to any incursion from an invasive species. As well as being light, the tunnels had to be durable to stand the test of time – and after ticking all those boxes, they had to meet sustainability standards, not to break down into micro plastics and also be recyclable.

Over time, through the kokako project and other programmes, an increased understanding evolved on the significance of the tracking card data. Essentially the percentage of tunnels showing the presence of the targeted pest became a vital measurement index, referred to as the Small Animal Tracking Index, with other terms evolving including Residual Track Index, Rat Tracking Index (both RTI’s) and Tracking Tunnel Index (TTI), all referring to the same key statistic.

And so, the language began to shift from not just “how many pests have we killed?” to “how many pests are still out there to get?”

The indices are now used in various pest control management and research settings, where percentage levels of tracking have been identified as key thresholds and used as pest control targets which correlate to the breeding success of threatened species. Monitoring the pest side of this known relationship can be cheaper, more timely, and less invasive than trying to monitor the animals we need to protect. The tracking cards have also extended to the direct monitoring of positive outcomes as well – taonga endemic species such as lizards, weta and frogs.

On the back of the kokako project, the use of the Black Trakka flowed on to other major projects around New Zealand. Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari established one the largest pest-proof fenced projects in the world, with the 47km fence surrounding the 3400 hectare sanctuary – with the Black Trakka being a vital tool in the work to clear all pests off the Maunga (mountain).

Similar stories unfolded in other sanctuaries around New Zealand with The Brook Waimarama, Rotokare, Tawharanui, who along with Maungatautari all now continue using Black Trakka cards for ongoing monitoring and detection of any incursions from predator species.

New Zealand’s Department of Conservation also employ the tracking cards for ongoing detection of pest re-invasion following eradication on many predator-free islands around the country; also for data management on pest suppression across mainland New Zealand – as do local Iwi, District and Regional Councils.

The power and understanding of the indices extracted from the Black Trakka cards is continuing to evolve, as expert practitioners and researchers establish how the system is best applied in various specific environments, with different species of interest, and how the correlation between monitoring results and protected species outcomes can fluctuate throughout the seasons.

- Wild Kereru

- Tui as few have seen them

- Marcus Agnew

- Warren teaching children

- Hand feeding Kereru

Warren, along with his equally passionate wife Lois, started in their own backyard, establishing a natural haven for native birds around their home on the Mahurangi River, and gradually extending this influence into their wider community.

In the early days of the 1970’s and 80’s they would save anything that needed help, included young possums or wild pigs, but the focus quickly shifted to native birds, and their home became a drop off point for birds requiring nurturing back to health – including Ruru, Petrels, Kingfisher, and Kererū. (see videos below)

At certain times of the year, their backyard would be a cacophony of birdsong, with a hundred or more Tui enjoying the party around the bird baths and sugar water.

From quiet beginnings in their backyard, they took great joy in seeing Black Trakka tunnels and monitoring cards helping like-minded conservationists combat invasive species in many countries and Islands around the world, including those in Hawaii, the Caribbean, Australia, Faroe, around the UK, and other UK overseas territories including the fight against the infamous mice on Gough Island.

Today Warren’s son, Marcus, continues the family-run Gotcha Traps, along with his wife and three young daughters. Gotcha Traps continues supplying the Black Trakka to conservation projects, and supporting the drive toward New Zealand’s goal of Predator Free 2050.